A Matter of Trust - the challenges ahead for Exmoor's landscape

Can farmers build trust with ecologists and government to make the new Landscape Recovery Schemes deliver for Exmoor?

DEFRA’s Landscape Recovery Schemes (LRS) require land owners and farmers to link up and work together, because the minimum area for each scheme is big - 500 hectares (1235 acres). For Brendon Commoners on Exmoor, this means working with neighbouring land owners and farmers, the National Trust at Arlington and Exmoor National Park Authority, as part of the ‘Reviving Exmoor’s Heartland’ - a huge scheme spanning some 10,000 hectares (24,700 acres) of the Brendon Valley, Simonsbath and Challacombe, with twenty two participants so far.

Brendon Commoners recently held an event with the local farming community to discuss the impact and opportunities offered by the scheme - a once in a generation opportunity to rethink, reset and regenerate the Exmoor cultural landscape, for the good of species diversity, habitat and climate change.

A two year consultation period is needed as, once finalised, the scheme lasts for twenty years, so participants have to get their planning right. Decisions made now will have a dramatic effect on the environment and livelihoods of those who live off the land. Understandably, farmers are cautious and want to safeguard their future.

Calling the scheme Landscape ‘Recovery’ slightly raises the hackles of farmers who feel they’ve meticulously followed government directives regarding how to farm and shape the land over the years, through previous schemes. They’re keen to know how best to benefit the environment and climate change, while continuing to provide food security and quality - and ensuring they can make a viable living now and for future generations of farmers.

“Climate emergencies are real and we all recognise that now,” says David Westbrook of Natural England, which regulates the LR schemes for DEFRA. “It’s not just about wildlife, it’s also about recognising cleaner air, water and flood prevention. LR is a huge opportunity to design our own scheme for Brendon Common. Farming has to be at the heart of nature for this scheme to work - to deliver a step change for nature and climate in this area.”

For Alex Farris, Natural Environment Manager of ENPA, the core focus is to, “Protect SSSI areas and carbon sequestration, nature, climate and habitat. It’s an opportunity for everyone to work together, on and off the moor - with more trees, connecting coombes and woodland. Creating corridors to moorland, creating scrub and ‘edge’ habitat to bring wildlife benefits. There is varied farmland around the moor where we hope to do habitat restoration and enhancement. Re-establishing some lost species like the Marsh Fritillary butterfly and Black Grouse, and reducing rhododendron and other invasive species - Molinia (‘Purple Moor Grass) ’is still too dominant and an issue.”

“Landscape Recovery is not the best name, but what’s behind it is that both farmed and wild landscapes in Britain have suffered a life threatening dramatic decline in species diversity over the last decades,” says Marthe Kiley-Worthington, an Exmoor ecological farmer, ethologist and author. “Agriculture is the major contributor, by destroying habitats and the application of chemicals which flow into the water, air or stay in the earth, killing countless billions of small living things - fertilisers, pesticides, herbicides and medicines. Dung beatles are almost extinct because of wormers.”

Robin Milton, farmer and former Chairman of ENPA, says with LR trust needs to be rebuilt with farmers. “You can’t argue that there’s a problem with biodiversity, pollution and climate. But if you blame people managing the land in response to the policies put on them for years, you will not gain their trust. They’ve just done what they were told. There needs to be more trust and we are looking at setting up an environmental farmers group in the area, to protect cultural security. The younger generation of farmers will walk away if they can’t see a viable future.”

“If we want to see the results out of Landscape Recovery it needs a bottom up not a top down approach - how do we get something really happening on the ground and keep the people there? In 20 years, the government will be looking for results so you’ve got to get everyone engaged at base level. Financial pressures will determine land use and LR is dependent on government funding, which is not guaranteed - and DEFRA may yet have its budget reduced? It’s very difficult to guarantee continuity if people can’t see direct benefits from the schemes. There is work to do to make LR work on the ground.

A genuine desire to do good are the same for the ecologists, farmers and Natural England. It’s a huge challenge and I’m cautiously optimistic.”

So, is the government funding going to be there for the 20 year LR schemes?

David Westbrook says, “Yes, that is the idea. There is a pot of money.”

“It’s important to keep a wide genetic background, but that’s not necessarily commercially viable,” says Marthe K-W. “So, it’s clear that to increase species diversity, the management and money need to be there.”

Christina Williams, Vice Chairman of the Exmoor Society and proprietor of Molland Moor, says, “To manage moorland well for nature, you need grazing animals, farmers and disease control. The whole cycle is needed and farming is the delivery tool.”

“We have to eat, everyone has to eat, says Marthe K-W, “But just planting trees is not going to solve it. Ecological agriculture can help: Self-sustaining, diversified food production which increases net production, is economically viable, conserves species diversity and is aesthetically and ethically acceptable.

“Different species graze and use the environment differently. Sheep eat very close to the ground, which means they contribute to reduced species diversity on moorland. Cattle are less destructive but can cause poaching, yet they make paths for other species to follow, so have biodiversity benefits and costs. Deer and ponies will not penetrate thick shrub but do follow paths. Animals must have enough to eat and will do whatever they can to get it and may trash the environment if they’re hungry. So increasing numbers in particular areas to reduce a floral problem (like Molinia) depends on how much palatable food they have available.

“We can pool knowledge and work out the species and numbers to maximise floral biodiversity. The key to a thoughtful, diverse moorland future is cooperation between all those who have interests. Changing strategies every couple of decades is expensive, ecologically often ridiculous and disconcerting for graziers (like being paid to drain an area and 10 years later being paid to block up drains). They must be paid for their efforts.”

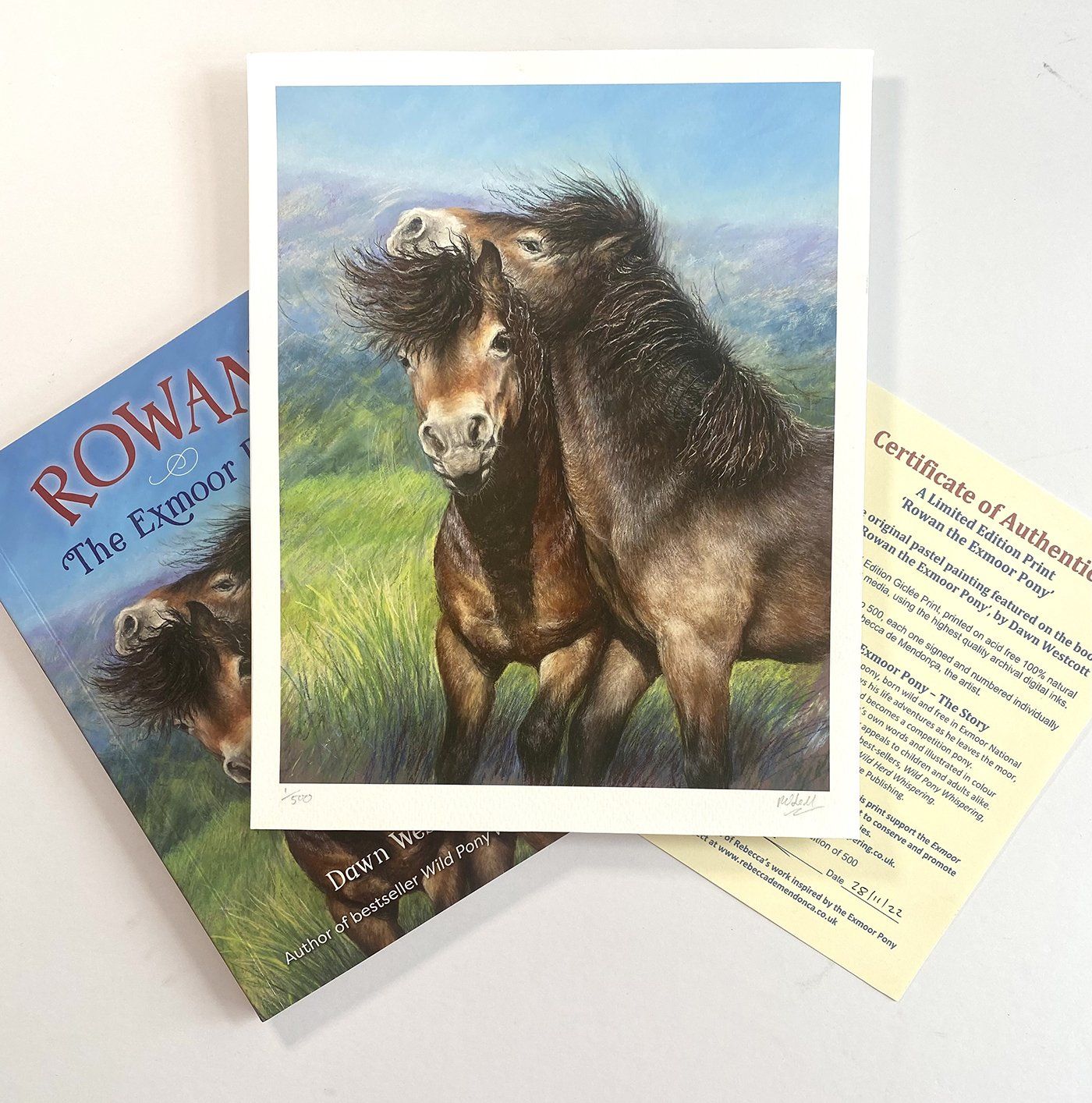

Maria Floyd, whose family farm cattle and sheep on Brendon Common and have the UK’s largest herd of free-living Exmoor ponies, wants to know if the LRS will aim to protect and prioritise native breed conservation - and this remains unclear.

Robin Milton points out that anyone setting up a native breed needs continuity and to know they’ll be recompensed for what can be expensive and difficult management that is not commercially viable. “When out on the moorland the reality is that free-living native breeds can’t just be brought on and off according to specific desired dates. They must be able to live out there and acclimatise - or they die. You need flexible management, where stock can go out earlier or later, as the weather allows - depending on conditions, not a prescribed dates system. Nature objects and makes its own mind up. We’ve got to be flexible enough to work with it. Invasive grasses like Molinia probably can’t be controlled in a warm/wet climate just by burning - we need to graze it too. We’ve become overly concerned to remove stock from the moors, but the problem now is finding enough farmers with enough stock to graze them.”

David Westbrook, from NE said, “That needs to be part of the discussion. We mustn’t be too prescriptive. We need to think about what climate change means in this process and be more flexible on what’s favourable for SSSI. The last thing I want is an on paper prescription to hold up future progress. “

With regard to introducing new species, Alex Farris said, “The Marsh Fritillary Butterfly has lots of potential with LR, particularly in land off the moor to create habitat for it to thrive.”

Other species being looked at are Pine Martins, White-Tailed eagles, beavers, Black Grouse, Hen Harrier and Curlew.

“On balance, Pine Martins are very good for biodiversity,”said Alex. “By predator behaviour, they’ll bring resilience to biodiversity. They’ll have an impact on the grey squirrel population.”

Marthe K-W advises caution about reintroducing Pine Martin, “It will be at the cost of some rare species. You need to be very careful.”

Christina Williams agrees, “Ground nesting birds are an issue with Pine Martins - the situation with Capercaillie and Pine Martins in Scotland is scary. We need to be honest about dogs, people and foxes as predators, too.”

Ruth Shippobotham says that at NT Arlington, “We want to improve the habitat and see what the land supports, see what turns up - we want to develop a holistic approach, increasing insects. LR can be what you make it and we’re still learning what’s possible. The real challenge is that we only have two years to put it together.”

While tree regeneration is a major aim of LR, there are concerns that fencing off areas of young trees will compromise grazing areas and re-route wild deer into areas they’re not wanted. “It’s perfectly possible to grow trees without excessive fences, by establishing them in appropriate places and using electric fencing,” said Marthe K-W. “Areas where grazing animals rarely go are obvious spots to scatter seeds and plant trees, ie, steep valleys with bracken and gorse, which can act as ‘nurses’ for trees provided there’s not too much grazing pressure.”

Sarah Eveleigh of Farming In Protected Landscapes said, “Deer management on Exmoor is very sensitive and we’re trying to develop a brief for the effects of deer on land with tree regeneration and come up with a plan that works for everyone.”

So how does the Reviving Exmoor’s Heartland group see the future?

“Ruth Shippobotham says, “A lot of work has gone into developing plans with NT tenants. Each tenant needs to look at a plan that works for them and we need to look at where we can offer suggestions. Like getting tenants to align and work together for better payments. We’re looking for greater connectivity and to share learning opportunities and best practices for participants in the scheme. There’s already a lot of collaboration between the NT and ENPA. It’s not just about the next five years, it’s also what happens in the final five years.”

David Westbrook says, “For Natural England, it’s about restoring nature at landscape scale. It’s the best shot we’ve got at a liveable future with viable businesses - having a future, a really good future.”

Ben Williams of the Badgworthy Land Company says, “Landscape Recovery is an opportunity and it’s up to us to use it, to do something special. It won’t work without the farming community having a viable business. We need happy, healthy farmers who can see their children taking over the farm. We need collaboration.”

“It’s about going forwards and learning lessons from the past,” says Alex Farris. “Not about blame. Learning from each other and working together and creating a LR scheme that’s more resilient to cope with climate change.”

The general consensus from the panel and audience discussing the ‘Reviving Exmoor’s Heartland’ scheme is a genuine enthusiasm to collaborate, share knowledge and do the best they can collectively to make the right decisions for this precious area of moorland and farmland. Producing the desired results for climate change, environment, habitat, biodiversity - and the people and animals living off it, for generations to come. An enormous opportunity - if trust and collaboration can be established and maintained.

This article appeared in the Western Morning News on 2 October 2024.

Photos by Sarah Hailstone 'Exmoor With Jack'